Background

Choosing a new accounting / finance system that is fit for purpose in a charity can be a daunting exercise. Unlike commercial entities, charitable organisations tend to have multi-faceted reporting requirements, from different stakeholders, which put a lot of pressure on their finance and management teams. A small or medium size charity will probably need to report on:-

- Income and expenditure in their natural headings, which may be sub-divided into headings that are more relevant to their internal management;

- Sub-categorise income and expenditure by activity (fundraising, charitable activities, governance, support costs) which may not necessarily be the same as those in a) above;

- Categorise income and expenditure in accordance with the headings for a donor report – which may be different to both 1) and 2) above;

- Split of restricted versus unrestricted income and expenditure;

- Some also split of the balance sheet between restricted and unrestricted assets, liabilities, and funds.

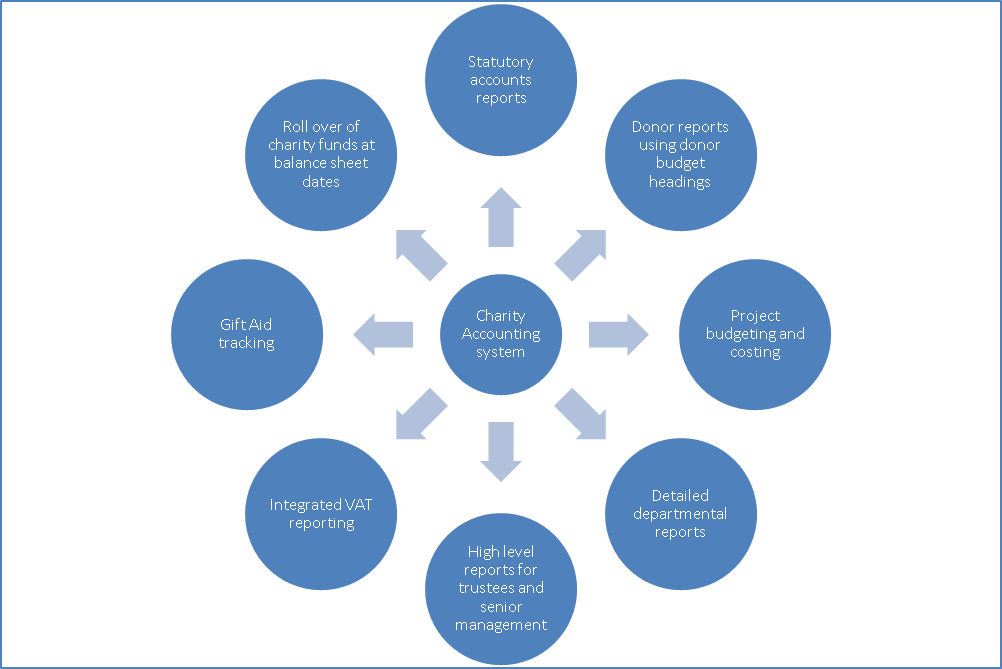

Any good finance system for a charity should provide multi-dimensional views of data so that a single entry can be categorised in multiple ways to fit the different reporting requirements.

Unfortunately, the majority of finance systems on the market are built for commercial organisations. There are very few which are customisable enough to cater fully for charity needs.

Other than price, we have listed below some considerations for choosing an accounting and finance system for charity, which management might find helpful when selecting the next system for the charity:-

Functionality and setup |

Considerations |

| Parent-child structure in the nominal codes | This can be helpful in creating report views that are based on the chart of accounts – e.g.

Ø The SOFA Ø Management accounts Ø Donor reports that follow the chart of accounts structure |

| Desktop versus cloud systems | There are many considerations here, but generally, cloud systems are likely to be more time efficient, not least for the ability to have bank feeds that allow for bank statement records to feed direct into the system. Preferences for control over your financial data is also key – i.e. having it on a local server where you can take your own back ups or in the cloud |

| Timesheet recording | If you need to maintain timesheets, could this be done within the finance system so that time reports can be linked to to other reports (e.g. donor reports)? |

| Multi-user access | Your requirements for internal and external users, different levels of access, your accountants and managers |

| Multi-dimensional analysis | To allow for income and expenditure to be analysed between e.g.:-

Ø Multiple restricted and unrestricted funds Ø Cases / beneficiaries Ø Types of work Ø Departments etc. Each block / categorisation required in reporting would need its own system object – otherwise it becomes impossible to distinguish the data in reports. |

| Sub-dimensions | E.g. where you have a parent activity and child-activities e.g. education projects as a primary activity, and school outreach and teacher training as sub-activities |

| Automatic funds rollover at yearend | Do you need this to happen automatically or can you live with a manual journal entry? |

| Software updates for new features as they become available | Free or payable? Is it an annual license? |

| Support plan options | Do you have to pay for after sales support or is it included? |

| User interfaces | How easy is the software to navigate? Can you see the full text of the list selections? Is it a system where you type any part of a field and select?

Multiple windows: can you view multiple windows at the same time? |

| Easy error correction | Can you easily correct errors or is the system too rigid? For various reasons, most small charities will need to have a fairly flexible system for error correction. |

| Search function | What can you search for? Full text versus ‘wild cat’ search |

VAT |

|

| Integrated VAT reporting | Particularly if your charity has exempt activities. As a charity, chances are you have outside the scope income (grants and donations), exempt supplies would bring into the picture partial exemption calculations… Not all systems will cope well. |

Budgeting |

|

| Multiple budgets | Can you have multiple budgets for the same period? Can you budget for multiple financial periods? |

| Project budgets | Can you have individual project / activity / fund budgets? |

| Donor budgets | Can you have budgets by individual donor? |

Other systems and processes |

|

| Integration of other internal systems and internal controls | Ø Payroll

Ø Timesheet recording Ø Stock management |

Reporting |

|

| Customisable reports | Different views of the same data or being able to change what you see on the report yourself. Pre-built report types, rather than pre-built reports (report types are more customisable to get reports, reports are just what they are) |

| Balance sheet analyses | By project or donor |

| Drill down to the transaction level | Is this possible on all reports or just some or none? |

| Donor dimension reporting | Where a donor report describes expenses differently from the standard chart of accounts, is there an option to slice information in this additional dimension at a transaction level and in reports? |

| Audit trail | Can you get a log of who changed what when |

| Expenditure to be analysed by funding source or donor | Most systems will be able to give a report of income by donor; many will not be able to give you report of expenditure by donor because they don’t have the ability to mark expenditure as being paid for by this or that donor. |

This is not an exhaustive list, but it may be a good starting point for assessing a charity’s requirements when considering a new finance system.